Conservation

Point of Views

Conservation

problems are an everyday concern for many people and organizations. The

concerns about environmental degradation are growing in a daily basis and so

are the efforts to defend nature and the environment. Unfortunately, the

general trend is, in my opinion, somewhat misguided. Scientists often do lots

of effort trying to learn from nature and we are obtaining increasingly more

knowledge about the environmental problems. However, due to the huge gap

between scientists and the general people, those researches often are lost in

the pages of a scientific journal that few people read or in a drawer of

governmental building not producing the results we expected.

Conservation

problems are many and diverse but they all have one thing in common: they

always have human origins. Nature, plants, animals and ecosystems in general

were doing great without us. The bottom line is that whatever the conservation

problem is, nature is not the problem, people are.

However, most conservation researches are oriented to manage nature. Wildlife

management, forest management, conservation of fisheries, and so on, always

deal primarily with managing the natural part of the system, the part that did

not have a problem!!

When one on has a

problem one can go to the root of it and eliminate the cause or one can do

half-as solutions and ameliorate the problem without ever solving it. Imagine

somebody that suffers of chronic headaches. There is probably a very good

reason for the headaches, they might be do to stress-related back tension,

sinus problems, dental issues such as grinding and clenching, lateral rotation

of some cervical vertebrates, as well as many other reasons not excluding a

brain tumor. One can try to seek the solution of the problem and try to solve

it or one can have a painkiller. This painkiller will not solve the problem but will let us get by. On time, the painkiller will not be

enough to take care of the problem and we will have to take higher douses of

painkiller or use a more powerful drug that can numb the pain. In the mean time

the problem can only be getting worse. If it is a dental problem it will not

improve, stress related pain will also get worse since the pain on itself

becomes a reason for stress, and, of course, if it a brain tumor this delay in

seeking a solution can mean a big difference. This is what I perceive as the

problems of our Tylenol approach to

conservation. While we have spent lots of efforts and resources in

sophisticated research related to management of habitats and nature, we have

given very little attention to the original cause of the problem.

I am not objecting

that we should learn about nature, genetic flow, habitats as well as resource

management. What I am trying to say is that, just like with Tylenol, we should

not expect to solve the problem by managing nature if we do not also do

substantial effort managing people. Unfortunately, managing people is not what

we (biologists) were trained to do and most scientist are reluctant in getting

involved in this kind of activities and often chose to stop short of doing what

needs to be done.

Now, what do

managing people involves? There are three basic ways to manage people. One of

them is religion, another one is education, and the last one is politics.

Religion is well known to be a powerful tool to manage people and modify

behavior of masses. Throughout history, religion has proven to produce great

result managing people; often times with unfortunate consequences however. That

is why I am reluctant to recommend that religion be used as a conservation

tool. I feel that it is similar to the Ring of great power of The Lord of

the Rings. In Tolkien’s story It has so much power that no body dared to wield it, even

the best meaning, and best prepared character, Gandalf, did not dare to wield

the power of the ring because he himself could be lured by its power away from

his original goals. This is the way I feel about including religion as a tool

for conservation, it has way too much power and a fear it what it might lead

to.

Education

The other tool for

managing people that most scientists feel comfortable is education. Most

scientists either by choosing or obligation are involved in teaching in

academic institutions however that is not really producing the result it

should. At the university level academicians might teach graduate students or

undergraduate students. At the graduate level, the universities, even

conservation programs, do not select students based on their potential to do

effective conservation but based on their potential to do basic research, just

like the people that do the selection, without really looking at what the real

needs for conservation are (Click here for a discussion

about it). There is still much to learn in that field.

At the undergraduate

level, I also feel that academicians are missing the main target for education.

College students are pretty much people that already

believe in the conservation causes, a bit like preaching to the converted. The

real need of education is toward masses of people that are not aware of

conservation problems and needs. Some universities and colleges require that

all students take some conservation or environmentally related class in order

to teach all the students the basic for conservation. While this is better than

nothing it falls to address the real problems. However, college students have

already developed their personalities and their priorities on life and are very

much established. On top of this they have the left over of a stubborn

adolescence plus the demands of the newly found adulthood (finding jobs,

spouses, etc) that occupies their mind and takes priority on their lives. I am

not saying that we should not teach them about  conservation in college but the efforts that we do in

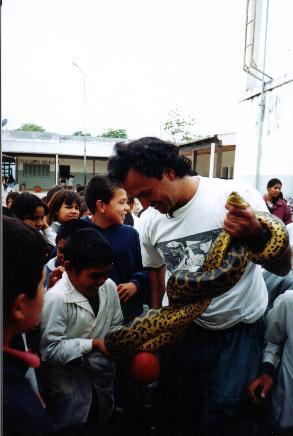

education are a lot better invested if we target the early

ages, grade school children that are avid to learn about life and their

personalities are developing. I contend that we must address the early ages

when we can try to instill love for nature. Conservation needs some sacrifices

and people will not do them if they do not love nature. Teaching kids to love

nature is the only way we can really address the global conservation crisis (click here for more about this). Unfortunately, although

some academics may agree with this, teaching children does not give tenure to

university professors and they do not see themselves bound to do this activity.

They believe that this is the job of grade school teachers. Poorly prepared,

worse paid, and overworked grade school teachers that is.

I believe that academician should work in coordination grade school teachers

and organize the work of their graduate students in that direction.

conservation in college but the efforts that we do in

education are a lot better invested if we target the early

ages, grade school children that are avid to learn about life and their

personalities are developing. I contend that we must address the early ages

when we can try to instill love for nature. Conservation needs some sacrifices

and people will not do them if they do not love nature. Teaching kids to love

nature is the only way we can really address the global conservation crisis (click here for more about this). Unfortunately, although

some academics may agree with this, teaching children does not give tenure to

university professors and they do not see themselves bound to do this activity.

They believe that this is the job of grade school teachers. Poorly prepared,

worse paid, and overworked grade school teachers that is.

I believe that academician should work in coordination grade school teachers

and organize the work of their graduate students in that direction.

Politics vs

Policies

The last tool to

manage people is politics. Most academicians are willing to get involved in

conservation policies but they will run for their lives if you mention the word

politics. In many places we have done superb conservation research and

recommended great policies for conservation that never got implemented. In many

case, it is like Whitten and Mackinnon pointed out (2001, Conservation Biology.15:1-3) a bit of displacement behavior, we feel we

are doing something good by coming up with the way to preserve biodiversity but

it is not really producing any results. Basically because our

findings do not produce definitive actions that lead to conservation measures

being taken. I really believe that we need to go the extra mile if we

want conservation to be effective. We cannot hope that somebody will pick our

policies and technical suggestions and make them into actions. The people that has the knowledge on conservation does not have

the interest in politics and the people that are politically savvy does not

know or care about conservation. Who is going to do it? I contend that it is

us, by virtue of having the knowledge, that are called

for to bring conservation to the political arena.

The 2000

presidential election in the US was a glaring example of this problem in which

the whole academic crowd fails shamefully in guiding environmentally oriented

voters to vote for the environment (click here for a

discussion). This addresses the difference between policies and politics.

It us understandable that scientist are reluctant to get involved in politics

not only because of all the bad reputation that politicians have but also it is

not something that we are trained to do and most of us do not know anything

about politics. However, What good is it that we

figure out how to save biodiversity if we do not get the elected officials to

implement our suggestion? Can we really protect nature without having political

back up to our policies? The current trends and experiences show that we

cannot. There is something very important missing worldwide and I believe that

it is it. In totalitarian systems it is all too easy to get conservation

policies in place once you convince the power holder but in democratic systems

that is not the case. If we believe in democracies, how can we expect

conservation to have some results without using democracy’s greatest tools (click here for a discussion)?

I know what you are

thinking: "we do not want to get into politics because politicians are lying scum bags that only care about votes". I will not

argue against it. But this is the good news: politicians do care about votes!!

Why is this important? If there is a political force asking them to take green

policies and implement environmentally sound policies they will do it. We will

not get conservation policies in place until we get the politics to turn

towards conservation. In other words we need to work to produce a tide o

environmentally oriented voters in order to make it happen. We do not have to

side with one party or the other, but we have got to stand by our cause. To use

politics as a tool for conservation is, therefore, a demand of our job

description and we need to do it if we want to move forward in this

struggle.

Most of us do not

want to learn something new that we not necessarily like and when we are never

going to be good at, but it will mean the world of a difference if we do it or

not. Back in 1993 I was presented with a similar dilemma. I was living in my

homeland of

-mail to Jesus A. Rivas